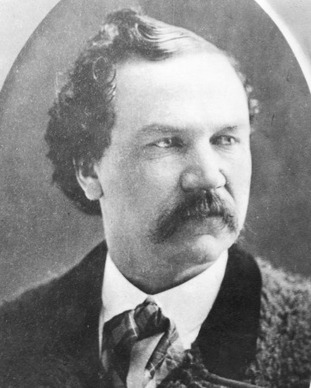

Samuel B. Parrish

(1836 – 1897)

Chief - December 2, 1884 – July 31, 1892

(1836 – 1897)

Chief - December 2, 1884 – July 31, 1892

Samuel B. Parrish was born in Piketown, NY in 1838. Two years later his father Rev. Josiah Parrish, a Methodist minister, came to Oregon, by way of Cape Horn, as a missionary with his young family. The elder Parrish acted as Indian commissioner for several years and his son worked as Indian commissioner in Malheur County for a couple of years before settling in Portland to run a mercantile store. Samuel Parrish was successful in business and very active in the Republican Party. In 1881 he was appointed Weigher and Gauger for the Customs House, a position he held until he was chosen Chief of Police in the tumultuous City Council meeting that deposed Chief Watkinds and began the impeachment of Mayor Chapman.

Although he had no experience in law enforcement, Parrish brought much needed stability to the Police Department. His effectiveness was hampered by the small number of policemen on the force and the unwillingness of the City Council and the newly reformed Board of Police Commissioners to pay for an expanded force. The 1880s was the decade of largest population growth for Portland. The city’s population grew from less than 20,000 to nearly 50,000 by the end of the decade. The police had their hands full trying to keep order in the Tenderloin and the North End and their street cleaning and sanitation duties were left behind. By 1889 the Oregonian declared Portland “the most filthy city in the Northern states.” The wealthy had begun to move their residences to the west of downtown and the increasing sprawl of the city stretched the police force even further. Parrish had to deal with growing violence in Chinatown as aggressive new Tongs, such as the Hop Sing began to challenge the older, more conservative Chinese societies for control. Parrish had to deal with the shootout in front of Frank Woon’s Restaurant in 1888 and other high profile murders, such as the murder of fourteen-year-old Mamie Walsh. During that case Parrish had to protect the main suspect from a lynch mob.

In 1889 Parrish began requesting funding for a patrol wagon. Up to this point police had to take arrestees to jail by walking or by commandeering whatever transportation was available; on at least one occasion that meant carting a drunk to jail in a borrowed wheelbarrow. The police department finally got a patrol wagon in 1890 and for years it was used to take officers to patrol beats and transport arrestees to jail. It was also used as the city’s ambulance. Starting with one patrol horse, by 1891 Parrish had acquired five horses and established the first horse patrol. By 1892, when Parrish was removed from office the horse patrol had ten horses. Another innovation Parrish introduced was the Police and Fire Telegraph and Telephone call box system. With call boxes located throughout the city the new system allowed police officers and firemen to keep in communication with headquarters from anywhere in the city. This was a huge technological leap for the police force and provided much better law enforcement coverage.

Parrish served as Police Chief for eight years. He was removed from office after the election of 1891, when the “Reform Ticket” came to power and the City Council was expanded to sixteen members. The Oregonian reported that Parrish had little to show for his time in office, because he hadn’t made money from his position the way his predecessors had. He stayed in office for several weeks after the appointment of Chief Ernest Spencer, to help the new chief learn his duties. After serving as Police Chief, Parrish managed the German Remedy Institute, located at SW First and Pine. The German Remedy Institute provided cure and support for addicts of “liquor, tobacco, opium, morphine and cocaine.” In 1896 Parrish was appointed bailiff of Circuit Court #2, a post he held until his death in 1897 at the age of 59.

Although he had no experience in law enforcement, Parrish brought much needed stability to the Police Department. His effectiveness was hampered by the small number of policemen on the force and the unwillingness of the City Council and the newly reformed Board of Police Commissioners to pay for an expanded force. The 1880s was the decade of largest population growth for Portland. The city’s population grew from less than 20,000 to nearly 50,000 by the end of the decade. The police had their hands full trying to keep order in the Tenderloin and the North End and their street cleaning and sanitation duties were left behind. By 1889 the Oregonian declared Portland “the most filthy city in the Northern states.” The wealthy had begun to move their residences to the west of downtown and the increasing sprawl of the city stretched the police force even further. Parrish had to deal with growing violence in Chinatown as aggressive new Tongs, such as the Hop Sing began to challenge the older, more conservative Chinese societies for control. Parrish had to deal with the shootout in front of Frank Woon’s Restaurant in 1888 and other high profile murders, such as the murder of fourteen-year-old Mamie Walsh. During that case Parrish had to protect the main suspect from a lynch mob.

In 1889 Parrish began requesting funding for a patrol wagon. Up to this point police had to take arrestees to jail by walking or by commandeering whatever transportation was available; on at least one occasion that meant carting a drunk to jail in a borrowed wheelbarrow. The police department finally got a patrol wagon in 1890 and for years it was used to take officers to patrol beats and transport arrestees to jail. It was also used as the city’s ambulance. Starting with one patrol horse, by 1891 Parrish had acquired five horses and established the first horse patrol. By 1892, when Parrish was removed from office the horse patrol had ten horses. Another innovation Parrish introduced was the Police and Fire Telegraph and Telephone call box system. With call boxes located throughout the city the new system allowed police officers and firemen to keep in communication with headquarters from anywhere in the city. This was a huge technological leap for the police force and provided much better law enforcement coverage.

Parrish served as Police Chief for eight years. He was removed from office after the election of 1891, when the “Reform Ticket” came to power and the City Council was expanded to sixteen members. The Oregonian reported that Parrish had little to show for his time in office, because he hadn’t made money from his position the way his predecessors had. He stayed in office for several weeks after the appointment of Chief Ernest Spencer, to help the new chief learn his duties. After serving as Police Chief, Parrish managed the German Remedy Institute, located at SW First and Pine. The German Remedy Institute provided cure and support for addicts of “liquor, tobacco, opium, morphine and cocaine.” In 1896 Parrish was appointed bailiff of Circuit Court #2, a post he held until his death in 1897 at the age of 59.